William Still and the Underground Railroad

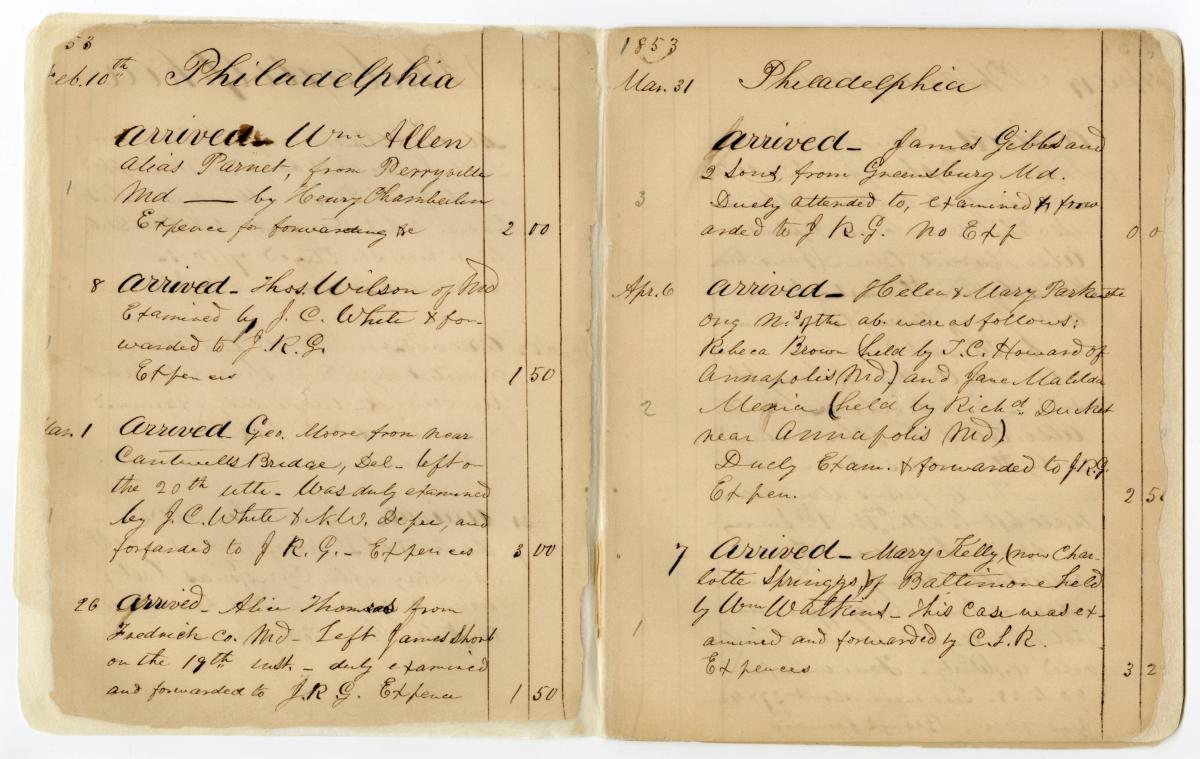

Born in Burlington County, New Jersey in 1821, William Still was a leader of the abolitionist movement who assisted hundreds of enslaved Africans in their escape from slavery along the Underground Railroad. Despite established laws prohibiting Black individuals, and especially enslaved Africans, from learning to read and to write, Still taught himself these skills out of resistance. He went on to use these skills to document those he helped escape in his self-published book The Underground Railroad, the only first person account of the Underground Railroad written and self-published by an African American. Through his book, we are able to visualize those who he helped and recognize the true impact of his work.

The Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad began as a series of common paths to freedom for those escaping bondage, and later became a robust network of resources for enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom. While many freedom seekers began their journey unaided and many completed their self-emancipation without assistance, this network was integral to the successful freedom of countless individuals. Beginning informally, after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 the Underground Railroad became deliberate and organized. Despite the illegality of their participation in this network, people of all backgrounds participated in this civil disobedience. Those escaping bondage traveled by land and see, by foot and by carriage, to locations all over the world--including Canada, Mexico, and Europe-- in order to gain their freedom. Those who attempted to escape faced great personal risk, as did those who assisted these individuals on their journeys, but they took on this risk in the name of freedom and justice for all.

William Still

William Still was as the youngest of eighteen children by Levin and Charity Still. Both parents born into slavery, Still's father purchased his own freedom, and his mother escaped her enslaver on her second try. In 1844, he moved to Philadelphia and in he 1847 married Letitia George, with whom he went on to have four children. Also in 1847, Still was hired as clerk for the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Still was appointed the chairman of Philadelphia's Vigilance Committee, an essential hub of antislavery activity.

Origins

In total, Still helped countless individuals from all across the Southern US on their travels along the Underground Railroad. This dataset recognizes 995 freedom-seekers he helped and documented in his book.

Hale Burton

One freedom-seeker documented by Still was Hale Burton. As recorded by Still, Burton fled the town of Kunkletown, in Worcester County Maryland, in 1860 to escape his enslaver. Burton was listed as traveling unarmed and by boat with a group of freedom-seekers including Henry Burkett & Elizabeth Burkett, Thomas Sipple & Mary Ann Sipple, and John Purnell. His age, literacy, enslaver, and any potential reward for his capture are unknown.

Hale Burton's Travels

With a total of thirty dollars between them, Burton's group purchased a small vessel for six dollars and began their journey to Philadelphia, PA. En route, they encountered a group of white men who attempted to overtake their boat. Despite being unarmed, the freedom-seekers defended their vessel and continued on. Eventually, the group landed on an island off the coast of Cape May, NJ. Here, they used the rest of their money to have the captain of an oyster boat to take them to Philadelphia. With the captain's help, they all arrived safely in Philadelphia, where they were forwarded to another agent of the Underground Railroad in Elmira, John W. Jones. A letter from John W. Jones to Still dated June 6, 1860, details their successful arrival.

Travel Patterns

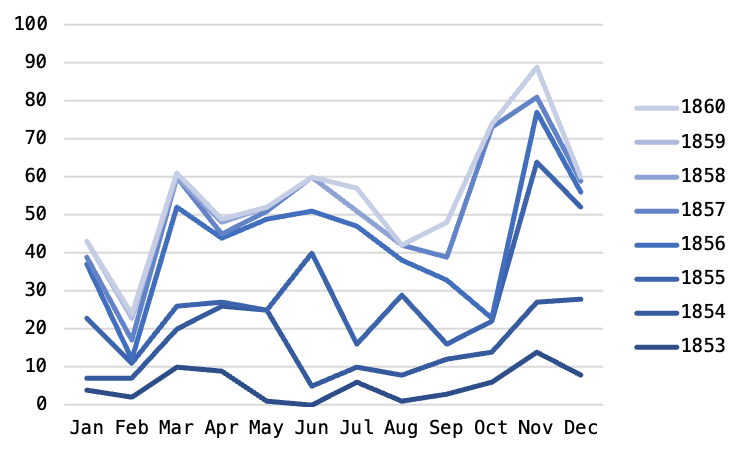

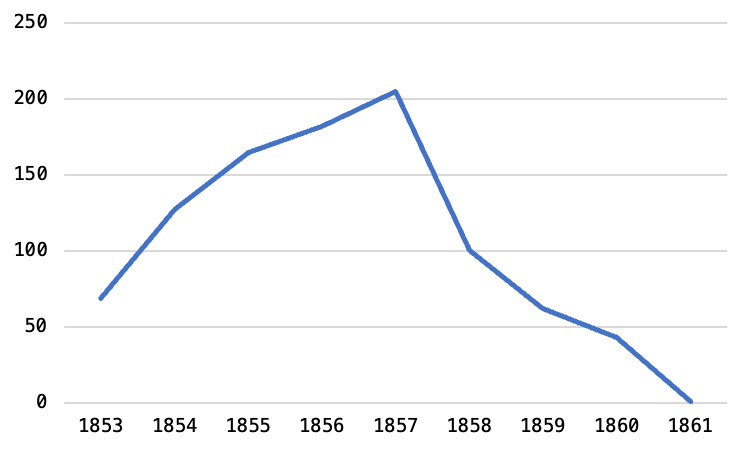

Spanning from 1853 through 1861, Still's records help us uncover some of the travel patterns of the Underground Railroad:

Notably, when analyzing year-by-year (below), we can see that Hale Burton's journey was towards the end of Still's documentation, during a period of sharp decline of freedom-seekers.

Still recorded helping the most individuals seek freedom in 1857.

When looking at the data month to month (right), in 1853 and 1854 there is not much measurable monthly difference in freedom-seekers.

But from 1855 on, the total number of freedom-seekers peak in November and December and experience a sharp decline in January and February.

Transportation

Traveling hundreds of miles, this journey was not easy. Still was able to collect transportation data from 313 out of the 995 documented freedom-seekers. Transportation methods noted by Still include boat, carriage, foot, horseback, railroad, scooner, skiff, and steamer. Unlike Burton, the majority of recorded individuals traveled by foot.

Enslavers

In the data for 65 freedom-seekers, Still also documented the enslaver from which each individual was escaping.

It is notable that there is not much data for this compared to the rest of the dataset.

Perhaps this is due to the possibility that many individuals seeking freedom might be afraid to document their enslaver.

Despite this, from what we do have, we can see that many freedom-seekers were escaping the same enslavers.

Here, we visualize the enslavers from whom five or more freedom-seekers fled.

Breakdowns

Through Still's data, we are also able to identify general demographic trends of those whom he helped:

Of these individuals, 23.5% were women,...

11.5% traveled with children,...

only 6.6% were classified as "literate",...

3.2% were documented as being armed,...

and 6% had a documented reward posted for their capture. Of these, the average award offered was $332.

Freedom

As a result of his bravery, William Still helped change the lives of countless individuals. His further commitment to documentation allows us to continue to recognize his lasting contributions to our nation's history today.